Is Shoal Creek A Suspect Name?

October 15, 2016 | By Shoal Creek Conservancy

This blog post was written by Andy Sobchak. To learn more about the author, please visit this site.

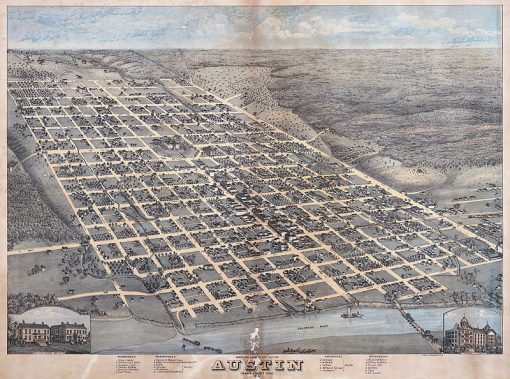

The etymology of Shoal Creek’s name is arrow-straight. Despite early auditions on some old maps as Cascade Creek, Shoal Creek gained its permanent identity in the early 19th century for obvious reasons. “Perhaps it was Edwin Waller who gave the creek its name because of the many shoals in it,” wrote Leila Downs Clark in her 1954 dissertation, The History of Shoal Creek, “for he laid out the town in 1839, and drew a map in which Shoal Creek is shown and named as the western boundary of Waterloo, later Austin.”

Not much has changed since Waller’s day: The shoals of Shoal Creek remain abundant and, at times, sizeable. Shoals, which are depositions (or bars) of sand and gravel, can occur in almost any water body type and form in watercourses like Shoal Creek when soil from upstream in the watershed is eroded by fast-moving water and unloaded in areas of slow moving water. One need only peer under the Lamar Boulevard Bridge to see their scale. This scale, 176 years after Waller’s naming, was exactly what Tom Hegemier was pondering last summer.

Hegemier, Stormwater Practice Leader at Central Texas consulting firm Alan Plummer Associates Inc, was commissioned by the Conservancy to investigate if these shoals were contributing to recent flooding in areas south of Pease Park through downtown Austin. Speculation in the Shoal Creek community buzzed about the possible impact of these large gravel areas since they collect debris, provide purchase for new vegetation and ultimately block creek flow.

“[Our] study evaluated the potential floodplain level reductions resulting from removing sediment bars and woody vegetation growing in the bottom of Shoal Creek,” said Hegemier via email. If fingers pointed at the shoals as accessories to flooding, a long-term sediment and vegetation maintenance plan could be implemented to help reduce the magnitude of future events. The Conservancy released Hegemier’s team’s findings in October 2016 as Shoal Creek Debris and Sediment Inventory, 15th Street to Lady Bird Lake, Project Summary – Technical Memorandum.

Field mapping the size and location of the shoals and any obstructive vegetation was the first step in the study, a process completed in collaboration with City of Austin and Shoal Creek Conservancy staff. Modifying an existing floodplain computer model originally created by FEMA was the second step. Where the FEMA model included the shoals, Hegemier’s modified version scalloped them out, increasing channel flow capacity as he went.

A 1997 study of Lower Shoal Creek proved invaluable in helping Hegemier to mark historic deposition patterns and substantiate proposed changes to the model. “The most challenging aspect of the study was modifying the [model] to reflect the potential larger creek channel based on the potential removal of sediment bars,” says Hegemier, noting the irregular shape and location of the deposits required meticulous attention and model coding.

The study extended from 15th Street to Lady Bird Lake but focused upstream of West Avenue since no evidence of sediment deposition was found in areas below the West Avenue bridge. Hegemier’s modeling showed the maximum reduction of flood elevation due to the removal of the shoals was at Lamar Boulevard during the 10-year storm – a 0.44-foot decrease, or about 5 inches. “Thus, the floodplain depth [at the Lamar Boulevard bridge] reduced from 15.6 feet to 15.16 feet,” the study report notes. “This led to a 10-year floodplain width reduction of about 52 feet which occurred primarily in the parking lot south of the House Park stadium…For the 100-year storm at this location, the floodplain was reduced by about 2.5 feet.”

These reductions are not appreciable, and Hegemier goes on to say in the report that “an ongoing sediment management maintenance plan is not recommended.” But it is important to recognize why the flood elevation reductions were less than expected when massive amounts of material were proposed for removal.

As it turns out, the location of the shoals is key. The shoals weren’t significantly blocking the effective flow path of the creek and, instead, were located in low-velocity “backwater” areas upstream of bridges. “Thus, one could excavate large quantities of sediment from the channel,” Hegemier notes in the report, “but when the water level is controlled, or held higher by the downstream constraints, there is limited benefit to sediment removal.” If obstructions are found to block faster moving regions of the channel – the effective flow path – they could cause higher flood elevations and warrant removal, but these types of obstructions were not found within the study reach.

In short, the study suggests the shoals of Shoal Creek are not playing a significant role in the flooding narrative but it does cast a suspect glance at bridges as major players. To read the entire report and a complete list of Tom Hegemier’s recommendations, click here.